“I lay only alive to the comical predicament.” Moby Dick and Me in a Tent– Blog Post Number One!

I don’t care that much about pop culture. It’s not that I’m a culture snob– I just can’t keep up. And I’m bad with names. But I do hit it off with Melville. And Emerson and Whitman and most of the time Thoreau. And you know what? Despite the fact that they were a bunch of guys writing in the 1800s, they have much to say about life right now, our lives. And even though I first started reading them when I was a moody sixteen, they still speak to me (but not literally) in the best kind of ways– and they might speak to you, too. Listen up.

Even though Moby Dick is the “Great American Novel that Few People Have Actually Read,” and everyone loves to complain about the detailed chapters on whale-ness, or “cetology,” Melville is irresistible. Really. That’s why he’s showing up so much of late: in the recent best-selling novel The Art of Fielding, in Moby Dick reading marathons, and in the Studio 360 radio program. There is even a pod cast now, the Moby Dick Big Read, where each of the 135 chapters is read by a different person; you can hear Tilda Swinton say those famous first lines, “Call me Ishmael,” and John Waters reads the chapter “The Cassock” about the sailor who garbs himself in a whale’s foreskin.

And who can resist a guy who writes lines like these: “But even so, amid the tornadoed Atlantic of my being…while ponderous planets of unwaning woe revolve around me, deep down and deep inland there I still bathe me in eternal mildness of joy.” Wow. That’s alliteration. That’s beauty of language. And it’s Ishmael speaking, yes, but that’s Melville’s voice—and who doesn’t want to know a guy who can find joy amid unwaning woe? I do. And the book is FULL of lines like these.

I first got to know Melville, really know Melville, earlier this year on a solo camping trip to west Texas—it was my own rite-of-passage trip to wean my two-year-old from breastfeeding. We called it my “Wean About.” And the South Rim of Big Bend was calling me. It’s an 8-hour hike from the Chisos Basin to the South Rim and back, and I count it as one of the most glorious and rewarding ways to spend a day. I wanted to feel that crunch of gravel under my hiking boots over and over for hours and nothing else. I wanted to see the fat Mexican blue jays and the vast open purple and blue mountains of the Chisos. It had been a while, and it was time to return. Alone.

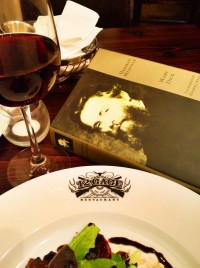

But on my first night in Big Bend, burrowed into my sleeping bag as the temperatures dropped into the 30s, I felt my aloneness more keenly than I had anticipated. There are no lights out there, so when the sun sets, it gets dark, very dark. But I had my headlamp on, and I had Moby Dick. And I had only just begun the book the night before in my little room at the Gage Hotel in Marathon, which was appropriate, because while there I got to read the chapter in which Ishmael meets the large black “barbarian” Queequeg at the old Spouter Inn in Nantucket. It’s a funny scene because Ishmael is forced to share not only a room but also a bed with this large tattooed harpooner (“Better sleep with a sober cannibal than a drunken Christian,” are Melville’s famous lines).

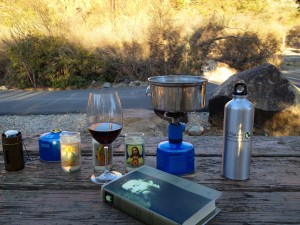

So that night in my tent, shivering in my sleeping bag, which keeps sliding towards the bottom of the tent because I had, unawares, set it up on an incline, I read the next chapter titled The Counterpane. In it, Ishmael wakes up to find not only Queequeg’s tomahawk by his side, but also Queequeg’s heavy arm draped over him in such a way that Ishmael cannot pry himself from its heft. Melville writes, “Upon waking next morning about daylight, I found Queequeg’s arm thrown over me in the most loving and affectionate manner. You had almost thought I had been his wife.”

This chapter is both sweet and hilarious. It’s like when a stranger on the airplane falls asleep on your shoulder and you may be stuck in discomfort but also not wanting to wake them up. There is humor and tenderness there. Ishmael’s amused acceptance and curiosity at his situation makes me really, really like him. He says, “I lay only alive to the comical predicament…. A pretty pickle, truly, thought I; abed here in a strange house in the broad day, with a cannibal and a tomahawk!”

“I lay only alive to the comical predicament.” Yep. That’s where I was: cold, alone and sliding down into a crumpled pile at the bottom of my tent, but I had my headlamp and I had Moby Dick. Here was this funny friendship growing not only on the page between Queequeg and Ishmael, but between the book and me. The humanity and humor of those two whalers thrown in together at the Spouter Inn warmed me up. Not only do Ishmael and Queequeg make the most of it, but they become kindred spirits. In the end they are fast friends who sometimes talk to each other with their foreheads pressed together— because that’s just how you do it back on the island where Queequeg came from, a literal tete-á-tete What would happen if I pressed my forehead against a friend’s next time we had a good chat? Ha!

Ishmael’s voice is so present and accessible, it surprised me. It’s easy to feel an immediate camaraderie. In The Counterpane, Ishmael speaks to us like a friend, one who confesses that he’s not even sure how to say what’s on his mind. About waking up with Queequeg’s arm over him, he writes, “My sensations were strange. Let me try to explain them. When I was a child, I well remember a somewhat similar circumstance that befell me; whether it was a reality or a dream, I never could entirely settle….”

Somehow this man writing about whales in 1850 seemed as if he were there with me in my tent in Big Bend, telling me bedtime stories. I didn’t feel so alone anymore. His voice was too clear for that. The tenderness between Ishmael and Queequeg was too real for that. And when I finally set down the book and turned off my headlamp, I was again taken aback by how deeply black everything went around me. It was a piercing blackness that I never see here in Austin. An unsettling nothingness. And then guess what happened? My eyes adjusted. I could again see just enough to make out the shape of my headlamp, just in case I needed it to get through the night, and I could also see the edge of Moby Dick lying next to it. And I understood that we are never really alone.